The following personal essay, “Falling in Love on Zoom,” by Kamala Puligandla, is an excerpt from Dyke Queen’s third issue, Recipes from Queerantine. Check out our interview about the issue with Autostraddle.

Falling in Love on Zoom by Kamala Puligandla

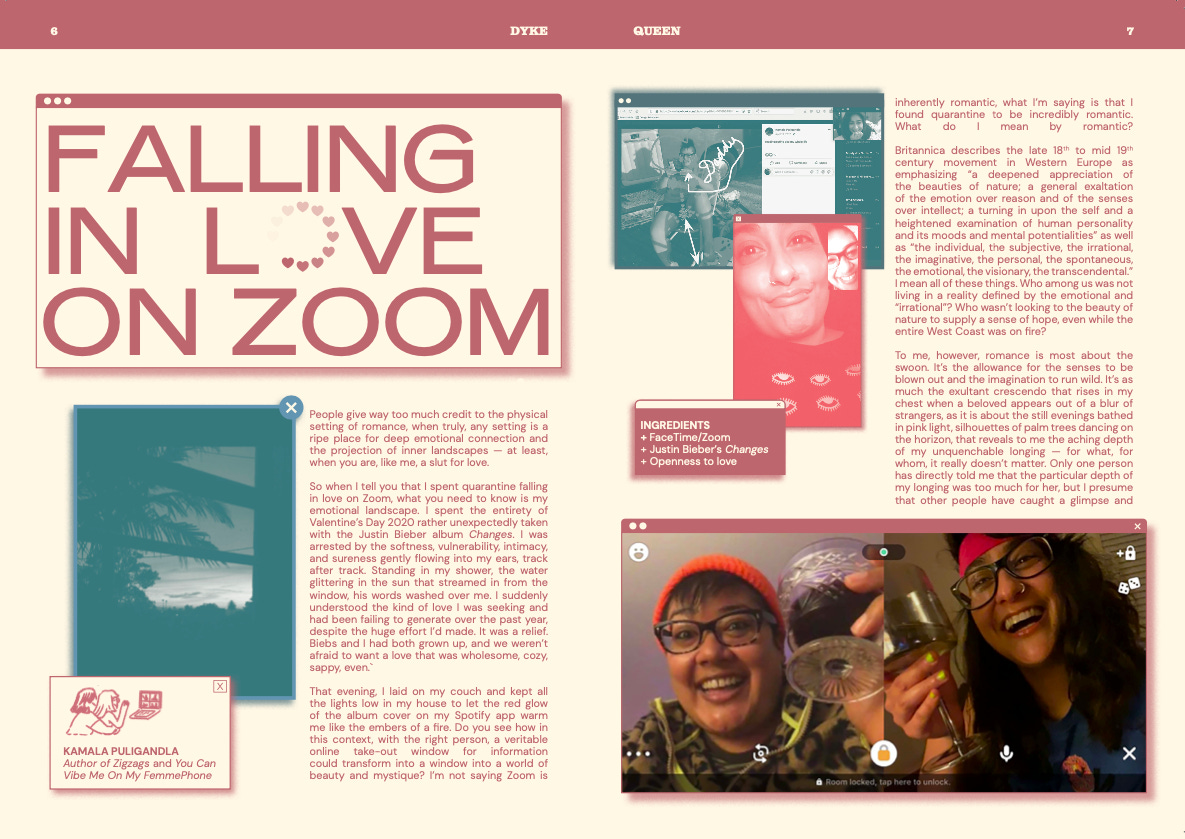

Zoom can been a wasteland — sterile, dry, aesthetically crude — it doesn’t really compare to say, the night sky lit up by fireworks on a hot summer night or a clearing beneath moss-covered pines at the edge of a coastal cliff. But people give way too much credit to the physical setting of romance, when truly, any setting is a ripe place for deep emotional connection and the projection of inner landscapes — at least, when you are, like me, a slut for love.

So when I tell you that I spent quarantine falling in love on Zoom, what you need to know is my emotional landscape. I spent the entirety of Valentine’s Day 2020 rather unexpectedly taken with the Justin Bieber album Changes. I was arrested by the softness, vulnerability, intimacy, and sureness gently flowing into my ears, track after track. Standing in my shower, the water glittering in the sun that streamed in from the window, his words washed over me. I suddenly understood the kind of love I was seeking and had been failing to generate over the past year, despite the huge effort I’d made. It was a relief. Biebs and I had both grown up, and we weren’t afraid to want something wholesome, cozy — even sappy — to keep us up at night.

That evening, as I lay on my couch, I kept all the lights low in my house to let the red glow of the album’s cover on my Spotify app warm me like the embers of a fire. Do you see how in this context, with the right person, a veritable online take-out window for information could transform into a window to say, a world of beauty and mystique? I’m not saying Zoom is inherently romantic, what I’m saying is that I found quarantine to be incredibly romantic.

*

What do I mean by romantic? Britannica describes the late 18th to mid 19th century movement in Western Europe as emphasizing “a deepened appreciation of the beauties of nature; a general exaltation of the emotion over reason and of the senses over intellect; a turning in upon the self and a heightened examination of human personality and its moods and mental potentialities” as well as “the individual, the subjective, the irrational, the imaginative, the personal, the spontaneous, the emotional, the visionary, the transcendental.”

I mean all of these things. Who among us was not living in a reality defined by the emotional and “irrational”? Who wasn’t looking to the beauty of nature to supply a sense of hope, even while the entire West Coast was on fire? To me, however, romance is most about the swoon. It’s the allowance for the senses to be blown out and the imagination to run wild. It’s as much the exultant crescendo that rises in my chest when a beloved appears out of a blur of strangers, as it is about the still evenings bathed in pink light, silhouettes of palm trees dancing on the horizon, that reveals to me the aching depth of my unquenchable longing — for what, for whom, it really doesn’t matter. Only one person has directly told me that the particular depth of my longing was too much for her, but I presume that other people have caught a glimpse and either doubled down or quietly closed some doors. I live to be moved. And I think it’s safe to say that post-Bieber Valentine’s Day, I’d found a new direction in which I wanted to be flung.

The defining feature of this direction was the desire to consume and be consumed with earnest, mutual hunger. In the song “Come Around Me”, Beibs sings in a commanding croon that falls into a pleading falsetto, “So when you come around me, do me like you miss me, even though you’ve been with me. Let’s not miss out on each other, lets get it in expeditiously.” That was the kind of romance I wanted. Something with urgency. Something where you could ask for a performance and enjoy it for the feelings it provoked, and not be a skeptic about whether or not asking for a performance meant this person actually did or did not mean it. Even in early spring of 2020, before the close, ever-present, daily reminders of death, it was starting to feel like a waste of my life to patiently wait for people to start not missing out on me.

*

The first time I met Sarah was in-person and pre-pandemic. There was some intensity in the way she was staring at me and in her bangs and her marketing lingo and her excitement that we were both half South Asian. The two of us were wearing brightly colored, short-sleeved button-up shirts and all of this made me pause and go, “Who is she?” This was during a job interview, and when I got the job, and signed my contract — laughing hysterically with a friend of mine at the clause about how dating your co-workers was not forbidden, but strongly discouraged, of which my friend said to me knowingly, “Please don’t do that” — I put the question of who Sarah was out of my head.

It stayed that way for many months. But I am an Aries. There are no inklings I have that die inside of me before getting tried out. I don’t remember why Sarah asked me to have a drink on Zoom after work — it was likely that there was something hilarious we needed to discuss, like the ignorantly racist descriptions of people that I was constantly editing out of the erotica series we had co-created. I do recall that our first Zoom drink was in March, right after LA (my home) and Portland (her home) had gone into strict quarantine. I had canceled a trip to the Bay Area and a birthday writing retreat in the desert I’d been looking forward to. “Absence is the opportunity to create space for something new,” I reminded myself in my journal.

During our first drink, which turned into three drinks, we laughed and laughed while examining photos of each other’s families, our younger queer looks, and sharing the latest updates on our romantic endeavors. After that, without thinking much of it, we just began video chatting every single day. We’d begin a call at 8 or 9 in the evening and not stop until 1 or 2 in the morning. It was exhilarating, it was the first gentle movement of my swoon. I always needed to hear another wildly dramatic middle school poem that Sarah had written about a single tear she’d shed at a dance or to learn one more stalkerish manifestation of her teenage obsession with Catherine Zeta-Jones. She always needed to hear another page from my latently gay memoir on a summer I spent in Malaga at seventeen, drinking Malibu con naranja. Sometimes she’d read my tarot and it would be a deep, vulnerable experience, other times we’d go on House Party to play Pictionary and make fun of each other’s bad drawings.

“I would never have time for this in regular life,” Sarah liked to remind me, as she sent me screenshots of her calendar from the previous year. I received these comments as a familiar warning, one I had received so many times from the variety of wary or unavailable women I’d been involved with all of my life. But there was something reassuring, all the same, about the depth of Sarah’s attention when we talked, our matching impatient need to know more, and the casual way she’d let me know, unprompted, when she didn’t think she’d have time to catch up that night.

*

The novel part about getting to know someone new on FaceTime and Zoom, was that I wasn’t meeting Sarah in any public space, where we could show off with impeccable looks or impressive bar choices or by accidentally running into the hip people we knew. It was so often the exact opposite. We were always at home, sometimes in the kitchen, usually in bed, rarely dressed to impress, and there was no reason to perform having a glamorous life — it was quarantine during a global pandemic. It was the opposite of all courtship I have ever known. Instead of gradually earning the trust to be allowed into intimate daily rituals, we began in our pajamas, sitting on our beds, like girls at a sleepover, trying to figure out how to convey our past public social lives, wildly dreaming about bringing each other there some day. There’s so much romance in nostalgically mapping out all the gay places you have ever been before and could have crossed paths, while simultaneously filling the empty unknown future with plans for where you’ll go next.

I took workshops with the poet Juan Felipe Herrera in grad school, and he was always coming up with beautifully strange ways to “derail” us from our intentions, into finding what our poems really wanted to be. Having my dating process “derailed” did reveal a new way for me to be moved by someone. It’s not that I wasn’t bowled over by her beautiful smile and the way she flipped her hair, but it’s not what made me call her. She always wanted to know I everything I felt and why. We dissected the tiny disruptions in our monotony: a visit from the hummingbird Sarah named Miranda, who lived in the tree across from her deck, the trio of ice creams I had just gotten delivered and wanted to try eating as one bite. The swoon I experienced was the surprise sensation that someone I was still getting to know, already treated me with the great care of an established friend, incorporating me into her the personal parts of her life with ease and joy.

*

Not that I’ve ever been good at recognizing when a friendship is glowing with romantic possibility, but I have to say it’s even murkier when your habitual daily rituals become a part of shared routine. It was normal for me to wash the dishes while we chatted and for her to take me with her on the dark walk from her apartment to her building’s laundry room. I think romance thrives on the lacks, on the holes, on missing pieces you have to fill in, on the parts of people you will never fully comprehend. So on the one hand, Zoom was the perfect medium for feeling the limitation, the distance between us while also allowing us into each other’s private sanctuaries. We could deep dive into our past dating lives, how we styled ourselves, what we wanted for our futures — and yet, I didn’t know what the back of her legs looked like. I daydreamed constantly about the mundane, like what it would be like to sit next to Sarah and put my hand on her thigh, which was just as mysterious and titillating as the idea of taking off her clothes.

On the other hand, I was left unsure about what part of our seamless connection was a digital illusion. What parts weren’t quite like I thought they were, and what were the differences between us that were easy to side-step on Zoom? Could we love each other with the same attention when we had in-person relationships again, when we weren’t the only thing in moving in a small frame in front of each other? It didn’t help that nothing felt “real” in any other part of my life. My first novel was supposedly coming out that fall, after years of delays, and I didn’t quite believe it. My job, which had originally been exciting, was less about editing and more about trying not to be undermined by the anxious whims of people. My ex-girlfriend, best known for her spontaneity, had become one of my most trusted and reliable friends. I sometimes talked to a friend of mine, who was unexpectedly falling in love too, and we’d say things like, “It’s so wonderful, but this, in quarantine?” and “I know that things will change” and “All we can do is see how it goes.”

But here’s the thing, when truly everything in the world is tenuous and uncertain, except for your 10pm Zoom date to watch Moana with a hot girl who wants to compare your brown hands and feet to the ones in the movie and giggle and cry and watch the “I Lava You” short at the end, AND THEN leave Zoom on all night in your bed, so you can have a sleepover and wake up together — what could be more certain? If the future was, indeed, a gaping maw, wasn’t I already giving the featureless, undefined cavern a strong piece to decorate around? I was beginning to understand that I was already completely enrobed in a Beiber style love affair. What had emerged from, what was for me, an entirely new way of spending time with someone I had a crush on, was also an entirely new kind of relationship.

*

When Sarah and I finally saw each other in person, I picked her up on a beautiful Saturday at the Burbank airport. I saw her standing at the curb with her giant pink suitcase and her hair looked even more overwhelming than usual. In stark contrast to the explicit sexual scenarios she liked to talk through over the phone, she didn’t want to kiss me. “Umm, I ate a quesadilla at the airport right before I came here,” she said through her mask. So I gave her the car ride home and the tour of my apartment and time in the bathroom to admire my plants and brush her teeth, to get adjusted to the hard reality of who and how we were in physical form together. And then I pressed her shoulders against the wall and promised her it wouldn’t be bad, before I kissed her. It was the softest, most supple kiss of my life. It was soft and supple — like eating a dumpling, biting into a mango, trying a new kind of oyster.

Of course, as much as I loved imagining what it would be like to smell her skin and squeeze onto my couch together, I was floored by Sarah’s presence — how much more vibrant the bougainvillea looked beside her and how vast the ocean felt when we walked on the cliffs above it. “I have to buy your espresso machine for my house so when you come to visit me, you’ll feel at home,” she said on our first morning together. And she did. And I did. Which is to say that the romance of quarantine, for me, is as much about the things that developed in the absences, as the sense I was being shown a whole new way for my desires to come into tangible existence — that my unquenchable want is also a form unrelenting hope.