I still remember when I saw my first Devyn Galindo photo. I was on my laptop and came across an article about We Are Still Here, Devyn’s stunning photobook featuring L.A. Chicanx youth. I was so blown away that I emailed them to say how much I loved their work. I never do that with artists I don’t know.

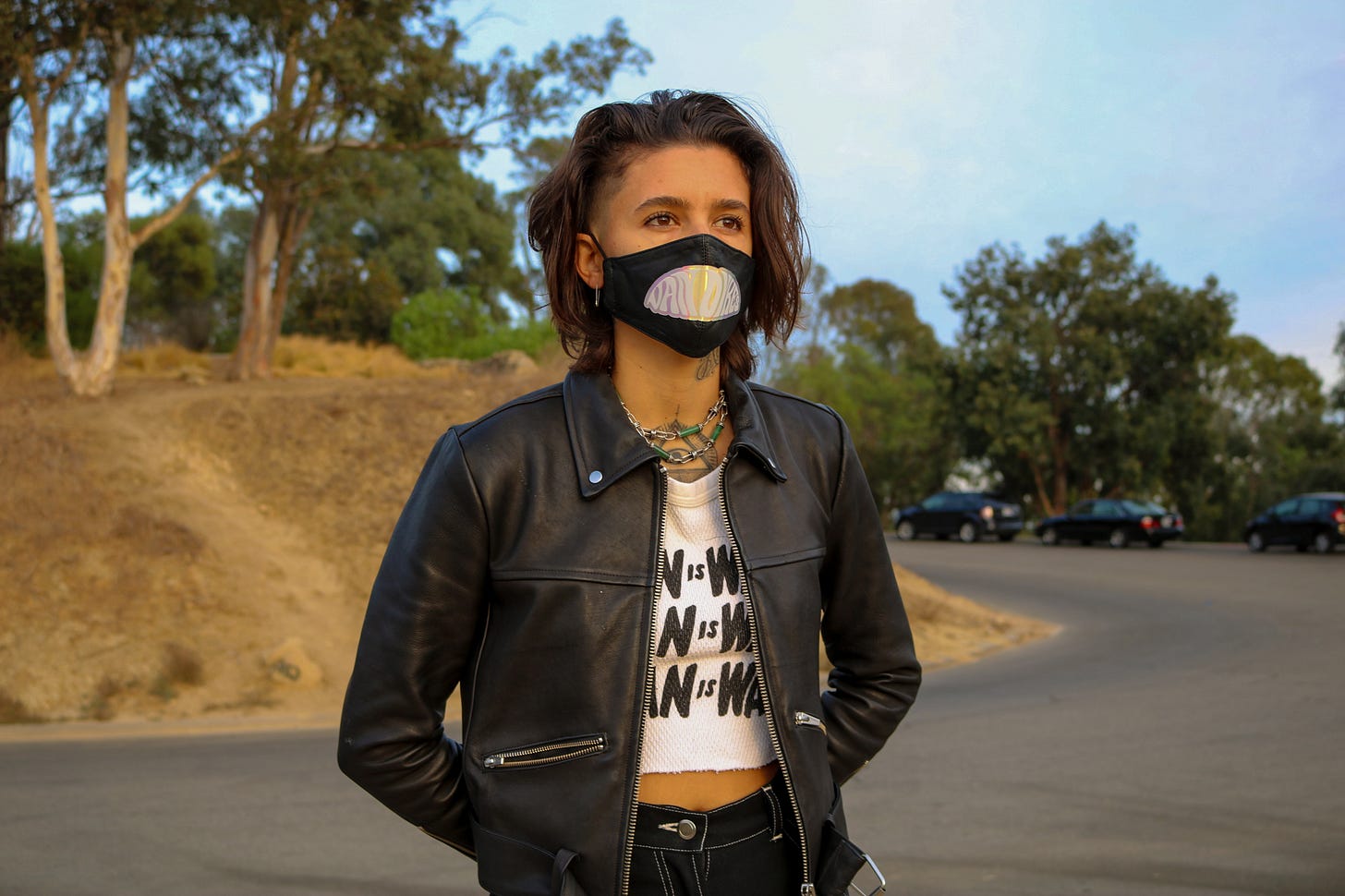

Devyn’s photos stick out to me stylistically, but also because of the subjects she chooses to photograph—queer and trans people, the Latinx community, people of color, and now queers communing with nature and travel in her newest zine, The Van Dykes Project.

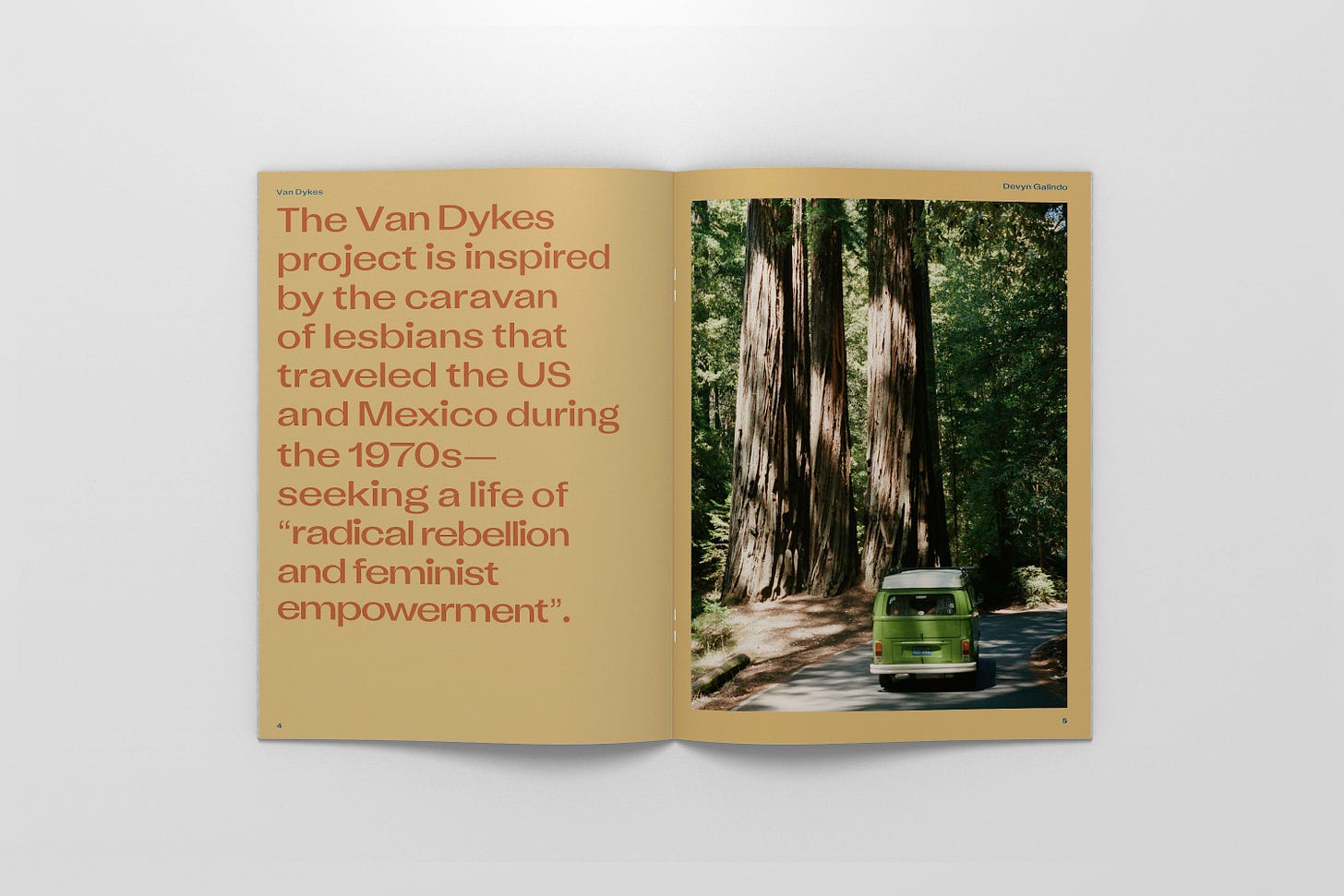

It hasn’t always been safe for queer people and people of color to take on nature and the open road in the way that we see our favorite characters do in films and novels. Devyn’s work challenges that notion with The Van Dykes Project—she goes deep into nature, into northern California, into Texas (in The Van Dykes Project Vol. 1), to commune with and interview queer people in places outside of the metropolitan cities of New York and Los Angeles.

When I first heard that Devyn was working on a project about The Van Dykes, I was ecstatic. I have my own special connection to the Van Dykes. Like Devyn, I first heard about them after reading Ariel Levy’s iconic 2009 New Yorker article “Lesbian Nation.” If you haven’t read Ariel Levy’s article, do yourself a favor and read it.

I first read the article in 2016 and shared it with my girlfriend at the time and my group of friends. We dubbed ourselves “Van Dykes” in honor of Lamar Van Dyke and all the dykes in the article who took to the road in pursuit of freedom—from a heteronormative, patriarchal world—and, most importantly, fun. My friends and I went on our own adventures, traveling to Mexico, northern California, and throughout Los Angeles—always taking the spirit of the tongue-in-cheek political conspirator Van Dykes with us as an added passenger.

As queer people we aren’t always taught about the queer ancestors who came before us and paved the way. Devyn’s Van Dykes Project keeps the legacy and spirit of the Van Dykes alive and introduces them to new generations of queer people who may be inspired to go on their own adventures like Devyn.

Read my conversation with the photographer Devyn Galindo below.

Editor’s note: This interview was conducted December 2020 in Los Angeles.

Yez: Let’s talk about the original Van Dykes from the 1970s—a caravan of lesbians that traveled the U.S. and Mexico seeking a life of “radical rebellion and feminist empowerment.” What about them inspired you to go on a cross-country road trip as an ode to them?

Devyn: I was already planning on going on a cross-country road trip and I wanted to interview queers along the way. The first Van Dykes [zine] was really important to me because I came out in the South and we were going to go through the South. I wanted to get in touch with Southern queers and see what their experience was like coming out as a queer person in the South. That was my first agenda.

While doing pre-production research before going on the trip, my ex-girlfriend and I found this article in the New Yorker about the original Van Dykes. I read that and I thought: this is crazy!

This article was from over 10 years ago and I thought it was crazy because this is exactly what we’re doing. Ours was a little more journalistic on the trip, not just wiling out, but we were so inspired by the fact that this had already happened. There had already been a caravan of dykes that traveled all over the United States and Mexico. We felt like we were very naturally following in their footsteps, traveling the same roads or like we’ve all been here before. I just felt like a lot of time melding together.

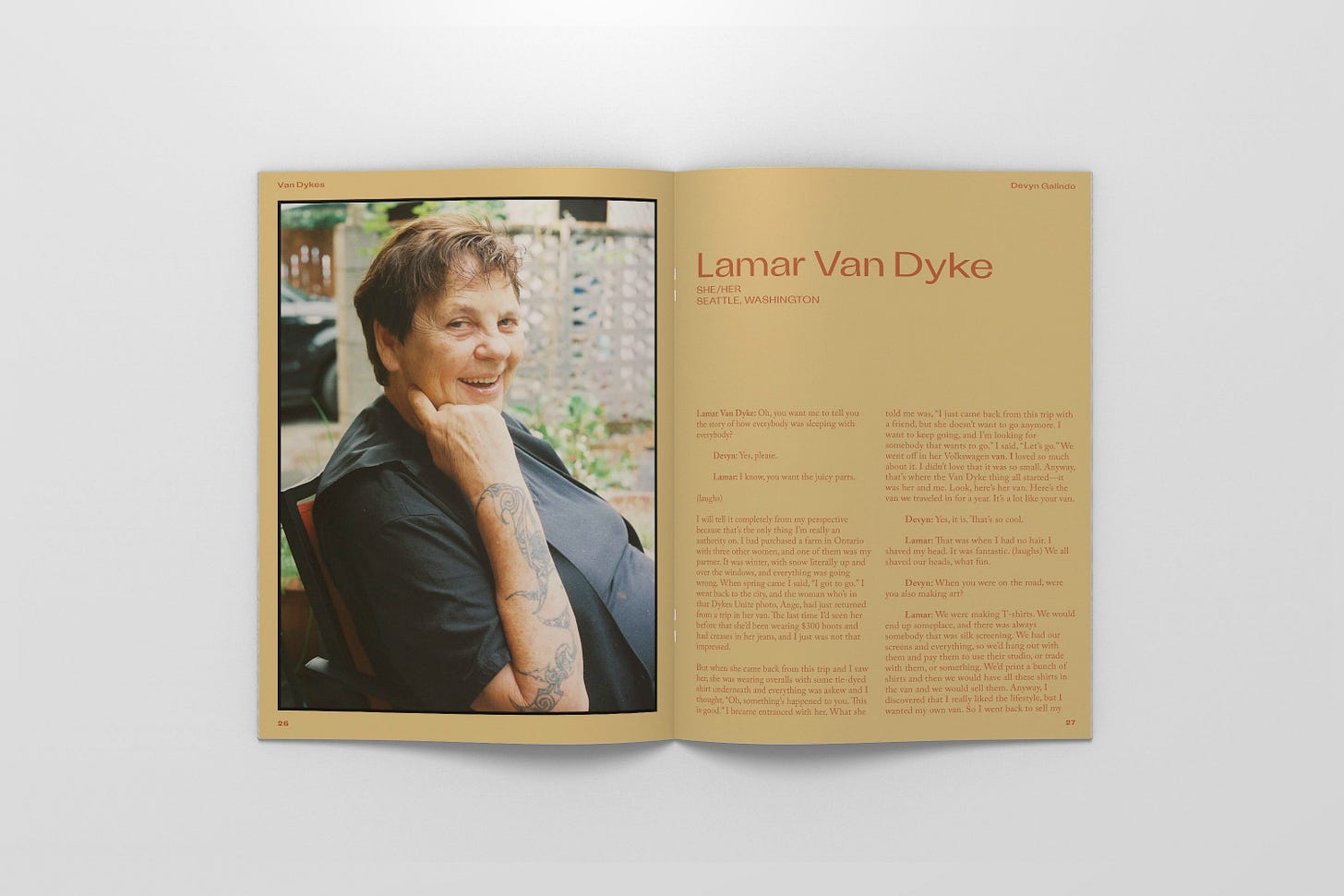

I care very deeply about carrying our ancestors with us. I’m trying to tell stories of the future but always with an understanding and reference to the past because we can’t be here without their existence and trailblazing. That was always in the back of my mind on the trip. I couldn’t believe that there was an original Van Dykes and we had to name this project as an homage to them. The second issue was really, really special because I got to speak with Lamar Van Dyke, who was one of the original Van Dykes. It felt full circle meeting Lamar and talking for hours. She rolled us a joint and we just drank wine with her and talked about what it was like to age as a dyke and what it was like to move through the world and still feel in a political rage.

From my perspective, being a dyke is very political and it has a new meaning in 2021 than it did back then but at the root of it we’re just trying to stand up for what we believe in.

Y: One of the most amazing things about your project is that you interviewed THE LAMAR VAN DYKE. She’s an icon, if we ever had one in our community. She is the original subject that inspired the New Yorker story on the Van Dykes, which is how you and me and the rest of the dykes who are obsessed with the Van Dykes first heard of her. How did you connect with her? And what did she think of the fact that you were so inspired by her that you started your own Van Dykes project?

Devyn: Can I say something else real quick? This is how weird and energetically insane this is, OK? I read the article and my friend came to the book launch, opened the book, and said, “Wait, Lamar! I know her. She’s one of my good friend's grandmother and I grew up spending time with her in Seattle.” I was like, what? It was just so full circle to have people in our community and that community. It’s all so small when you really think about it and we’re all so much more easily connected now. We can find each other now in a hashtag on Instagram. It’s great that we can do that.

Yez: What did she think about you making a project that was inspired by her and the rest of the Van Dykes from the 1970’s? It obviously touched you so much that you named this project as an homage to them.

Devyn: She was really excited. I definitely wanted to honor the incredible Van Dykes that came before us. From what I gather from the spirit of the Van Dykes, the more the merrier.

The Van Dykes as a zine is a collection of all of our stories. it’s just going to keep growing and bring in new people. Hopefully it will inspire more community. I want to do queer campouts in the future. I want to create more community-oriented spaces. Lamar loves this new generation of Van Dykes—she was pretty stoked. I gave her some Van Dyke hoodies. She gave me some of her shirts that said, “Van Dykes.” It was really really special and I love the relationship we’ve been building as intergenerational dykes homies.

Yez: Let’s talk about the pop-up you had for the release of the Van Dykes zine during quarantine in November of 2020. You brought out your 1970’s VW camper van and wheatpasted Van Dyke posters in Silverlake in Los Angeles. You announced it on Instagram. Was that the first Van Dykes event?

Devyn: Originally I was going to have a whole party at Milk Studios, but we had to find the right timing and stuff. I thought, you know what, let me just guerilla-style this, in the spirit of the original Van Dykes. Let’s just do it on the street. Let’s wheatpaste these posters and do a pop-up and try to create a little bit of community in a really dark and strange time. I know that we probably would have had more people come through if it wasn’t for COVID, but I was happy to see familiar faces. We’re not able to be at the bars, or be on a sweaty dance floor together anymore so I just wanted to see my community in real life even if it’s socially distanced. I had been craving that.

It’s been rough not being able to see people. We have our quarantine pods, but as queer people we have such a small portion of this world where we feel safe, so to not have those safe spaces right now feels hopeless. I think a lot of people have been struggling with a lot of mental health issues and in and out of depression during COVID. I went through a really bad depression and I don’t usually get depressed ever. I’m just trying to create things that inspire people. We’re almost through this!

YEZ: You’ve published two issues of the Van Dykes zine. This is the second one. What was the inspiration behind each issue? How will the Van Dykes Project evolve and grow?

Devyn: I see the Van Dykes zine as an ongoing project for probably the rest of my life. When we made the first issue, I had just gotten the van. I had just gotten into a relationship, and it was inspired by the spirit of that, you know? Let’s hit the road and you’re gonna be navigating these spaces as two queer women. Depending on how I present, I move through spaces in an unsafe way in the South. In her experience, she was moving through the South as a black woman so we were constantly having conversations - unpacking what it meant to be moving through these spaces and land where many of our ancestor’s blood is in the land. We tried to focus on stories that were in our immediate network and community.

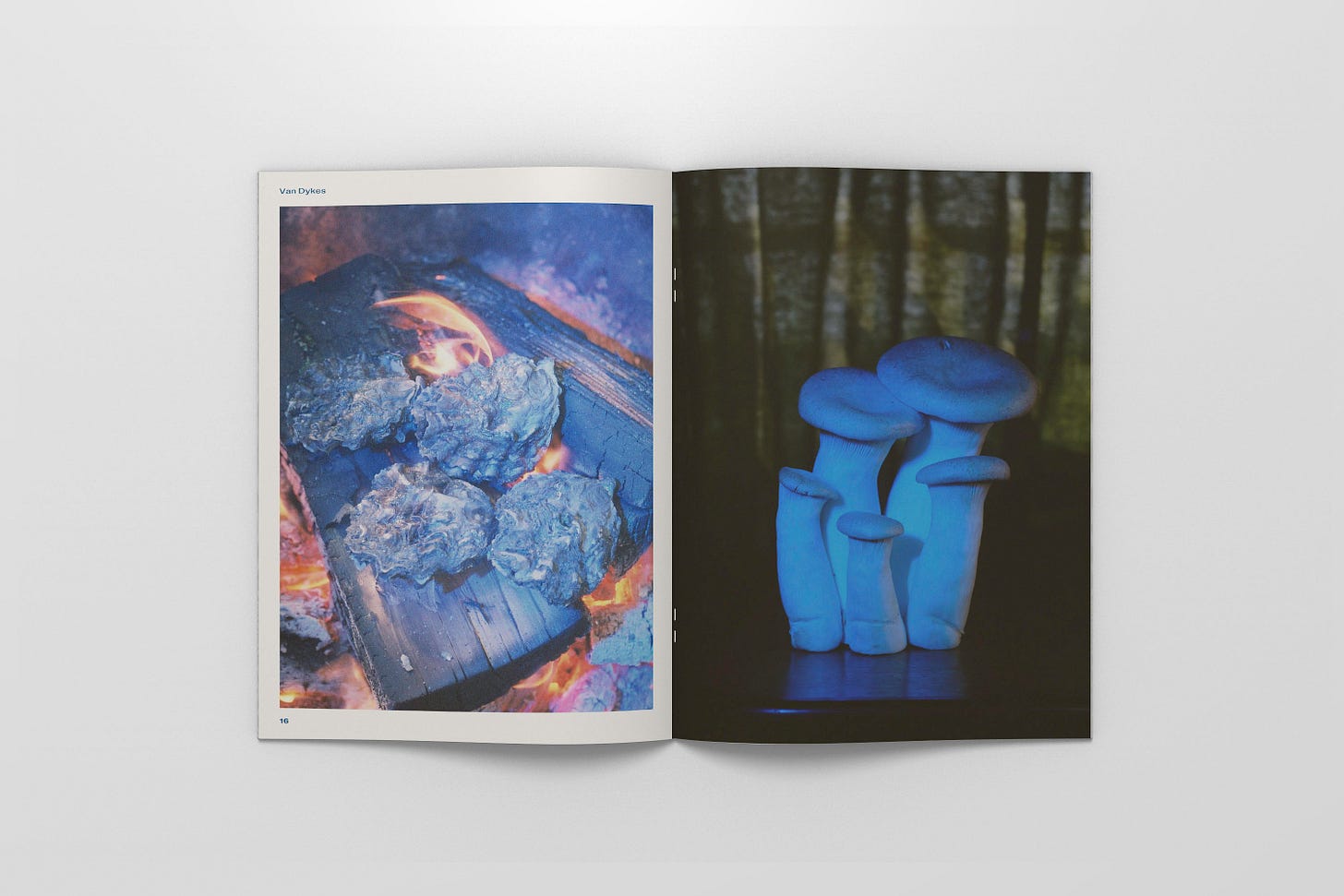

The first one took place over the span of three months. We were on the road longer; I was still figuring out the formula of how I wanted it to go. Hope was doing the interview portion. For this issue, I did the interviews. I had intimate conversations with folks and then I shot them. This one built off the last one. I learned a lot of what I wanted and didn’t want. I wanted to make it feel like it was a personal page out of my journal mixed with interviews and images of people so it has more of an edge. This time around, it’s a little darker and psychedelic, and experimental. It has more touch of the hand. I love how the first one turned out, but I think it was missing that for me.

I see the project evolving and hopefully gaining more collaborators; maybe even taking it internationally. I really want to do one in Mexico. Even if I can’t take the van, I would love in a post-COVID world to capture stories in the spirit of travel and meet new queers all over the place. I see it going in the direction of organizing queer campouts and more community-focused events so that we can grow it together. That would be my dream. I know there’s other dykes out there with vans, so we just gotta find them. Or a Prius, or whatever; I know people camp out of their cars.

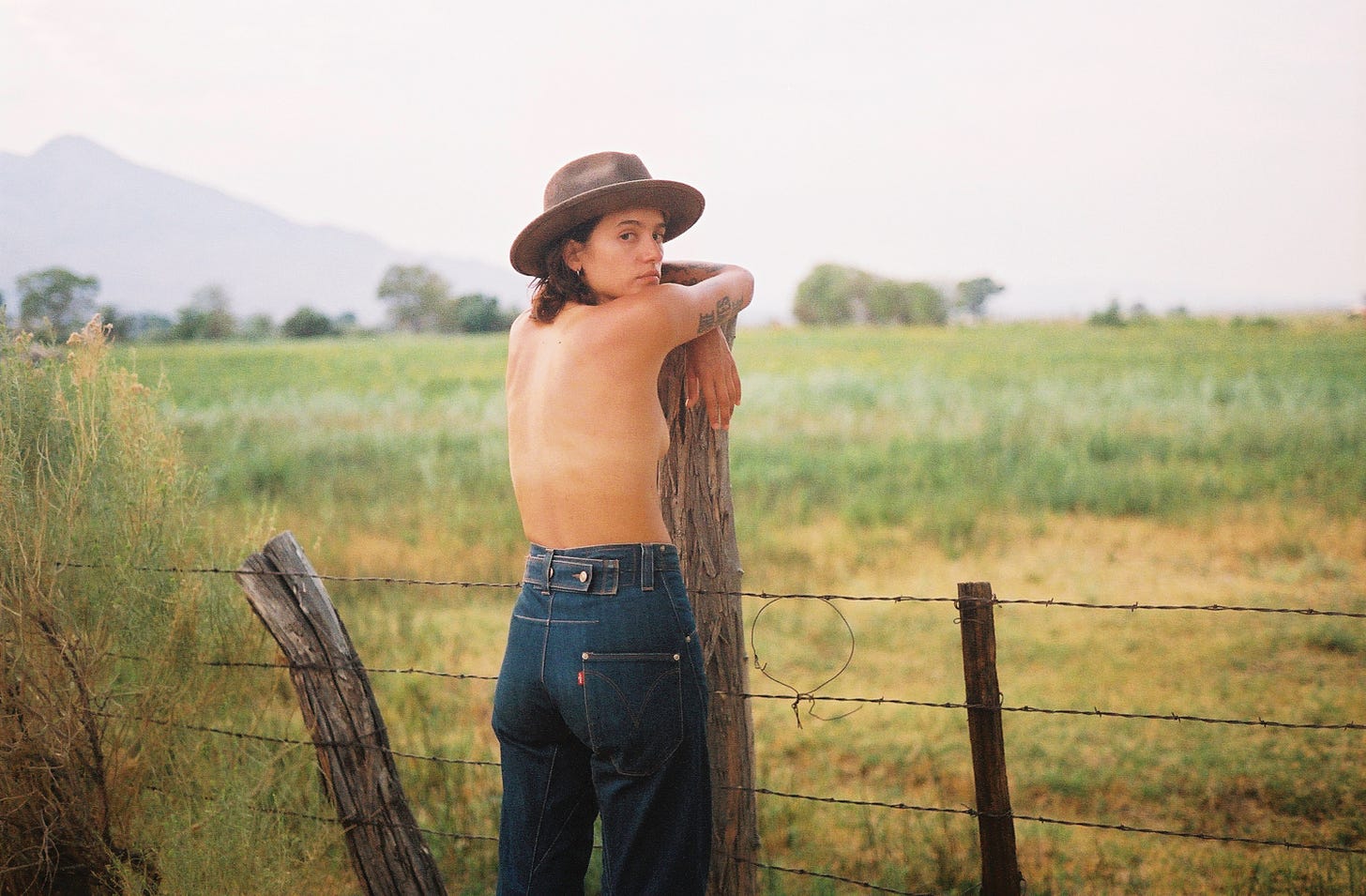

Yez: You’re a photographer. Let’s talk about the photos! They’re so beautiful. The photos are so intimate and vulnerable, whether it’s you skinny dipping with some of the subjects in your project, or your friend Erin coming back from foraging in the woods with blueberries in her hand.

I’ve been following your work since I first came across photos from your We Are Still Here project. It blew me away, and I emailed you when I saw those photos to tell you. I didn’t even know you, but I felt so connected to your photography that I reached out. What was your approach to making these images?

Devyn: How do I approach photography? Literally up until the time I started shooting this project, I was in a deep, deep depression. I think it was mostly because my biggest source of sanity is being able to create through whatever emotions I have and the fact that I felt like it was stripped away during COVID, was difficult. I couldn’t meet up with people. I couldn’t work. I couldn’t do anything. I just felt really stuck with no way to express those things. I went through a pretty rough break-up and then immediately hit the road. I felt like I had a lot to say and a lot to get out.

It felt like a visual purge for me to have my camera at all times and try to look for the beauty and inspiration everywhere. I know at my core that my purpose is to communicate that. I just tried to crawl out of my rabbit hole. My approach with this was just don't put pressure on it; just let it come. Let it flow naturally. Wake up, make art and don’t overthink it.

The people that made it into the book, I met randomly. It wasn’t premeditated. I was staying at an Airbnb that just happened to have two dykes running it. I ended up interviewing them; their names are Preston and Nicole.

And then Marie, this is like cosmic-level stuff, right? My friend and I had these paddle boards that we took all over the place. I was trying to exercise and make art everyday to just get my mind right. We paddle boarded for like four miles, and we’re not expert paddleboarders, so we’re dying by the time we get there. We look over and on the beach. We see these two women. They’re making out, and I was, like, we found dyke island! This is sick!

We paddle boarded all the way over and parked next to them on the beach. We ended up chatting it up. I took some photos of them and they’re in the book too. It just felt very cosmically aligned.

My approach to photography is to first observe and then ask permission to make images with folks. Make it as collaborative and easy as possible. I like it when people forget the camera is there and I can just capture a moment of who they really are. That’s the hardest part about making images in today’s day and age. Everyone is so ready to have their photo taken or they have a version of themselves that they want seen. I try to get to the core, like, who are you really and try to express that. The images come through the way they do because I’m sharing my vulnerable side of them and they’re sharing their vulnerable side of me. We’re in a state of rawness and that’s the space I try to make images in.

Y: You talk about “queertopia” in the zine. You ask your subjects to explain what it means to them. After going on two Van Dyke zine road trips, I’m curious—what does “queertopia” mean to you?

Devyn: To me, queertopia means moving in any space without fear. Having access to land and water with my community would be my version of queertopia, like a version of back to the land. But not too far from the city because I love the city. I love the information; the mind stimulation from the city. Having a farm would be really cool.

Y: That’s what the Van Dyke’s were all about—stopping on Women's Land and creating community with other women who were trying to thrive economically outside of of the cisheteropatriarchial economic world we live in. That same energy.

Devyn: I do think we’re living in a parallel time of a little bit of back to the land, like how there were those Women’s Land projects. Maybe land was a little maybe more affordable or attainable back then than it is now.

I would love, love for a portion of a future Van Dykes to find Women’s + Queer Land projects that still exist, I should say, because I think that it would be great to explore queer spaces in general. I know there’s some in Tennessee.

Yez: I’ve heard that some still exist, but it’s older women who have been living that lifestyle for a long time.

Devyn: If I had enough time and resources, I would love to try to track all that down and see what’s left. What future land projects are in the works. I do think as queers we live really alternative lifestyles in general so our family structures look very different. It’s more chosen and we can make it whatever we want it to be. I’m always talking to my friends, like let’s all get together and buy a plot of land. I see myself moving towards that probably in the next ten years or so.

Y: In the zine, you talk with two women who tell you about how they were disowned by their families for being queer. It’s important to cover stories like this because mainstream culture thinks that all queer people are safe now because of visibility, but that’s not the case. I thought it was really powerful to include their story in the zine. Here’s the direct quote from the interview:

“You come from a lineage of ancestors who were strong enough to stand up against not just society, but most times their family of origins. We have had to be willing to walk away from the families who raised us, and stand up to the abusive religious beliefs that tried to separate us from society and a spiritual foundation. You now live in a time where so much progress has been made. Appreciate it. Keep digging in and rooting down to the wisdom of your beings. Know that you are sacred and loved no matter what flavor you come in.”

“Remember that we are all traumatized to some degree or another just be being part of the Rainbow family. Try to have empathy and patience for one another when we’re exhibiting toxic behaviors or going through growing pains. Remember that hurt people hurt people; when a family member causes you harm, please remember not to take it personally. If we can learn to shift into love and kindness as much as possible, healing is attainable--it just takes time and love.”

Devyn: Despite the mainstream coverage we have now, it’s still very, very much a fact for a lot of people. Even in the microaggression. We still have so far to go and creating those healing spaces for our people is a mission the Van Dykes is about. Just like with We Are Still Here and the Van Dykes project, I want to leave behind things that in a hundred years somebody could pick up and say: we existed, this is our lives, this is our experience.

Yez: You describe The Van Dykes project as an object you want to be discovered by queer youth in a hundred years. Why is leaving an impact on the next generation important to you?

Devyn: I think that exactly what you were saying that I don't feel like our history is well-documented. There is a lot of amazing art that has come in the past and photos and things, but because we’re queer there’s less interest to archive it. There are archives like ONE Archives at USC. I wanna shout out ONE Archives because they are such an incredible resource.

It’s hard to find people that you can relate to, history where you can see yourself or see other people like you. You’re seeking community and you want to know how somebody else knew how to navigate the space. It just helps to know that you're not alone. The things that I choose to document are parts of my personal identity that I feel like I don’t have as much access to resources as I'd like.

Leaving it for future generations to just, like, who knows, maybe future generations could care less and they're just gonna be avatars on the internet.

For me, personally, I care a lot about queer history and documenting our stories. That is another reason I feel very much like a two-spirited historian in some ways.

Yez: The Van Dyke zines are so well designed and printed. Can you talk about your relationship with self-publishing? How can people support your work?

Devyn: It’s hard to know where to start, right? If you’re creative, it’s hard to know.

OK, I don’t have any contacts in the publishing world. I’m just starting from ground zero, but I can’t describe it. It just comes out.

I have to get it out of myself. I have to put it in something that is a book. I don’t know how else to describe it, but I think I find the design process to be really, really fun. I spend a lot of time with the images, laying them out, figuring out how I want the narrative to feel. And what the flow of the story is going to be; the visual storytelling throughout each of my books. I re-edit and I re-edit and I re-edit. Once I feel like it’s in a decent place I link up with a graphic designer.

I explain to them the project and they help me lay it out a little more to design standards. It’s always a nice collaborative process to have someone on that level working with you. Otherwise you second guess yourself or overthink things. It’s nice to have collaborators. I really enjoy that process.

I really believe in independent publishing and self-publishing because there’s no one telling you what to make. You have true freedom but it can be a little daunting because it’s expensive.

I have to pay all this money. It costs so much, but it’s so worth it.

It’s worth it to make the investment in your ideas and in yourself because it’s something tangible that people can have and see. Oh, this is your point of view? This is your perspective. Your story to tell.

I’d like other creatives to keep up with that. Otherwise you see the same thing. Publishers publish the same people. It’s always the same formula. So instead of getting mad about that, I’m making my own way. I’m carving my own path. That feels pretty good.

People can find my books at Printed Matter in New York or on my website devyngalindo.com or vandykesproject.com

Thank you for reading Dyke Queen. We have a new print issue about queerantine coming out soon. If you want to support us, share this post with a friend or become a paid subscriber.