What if the Virgin Maryam became pregnant because of a man who wouldn’t take no for an answer? What if Maryam never wanted to be with a man, not because that is how to be a woman the right way, but because Maryam was a dyke?

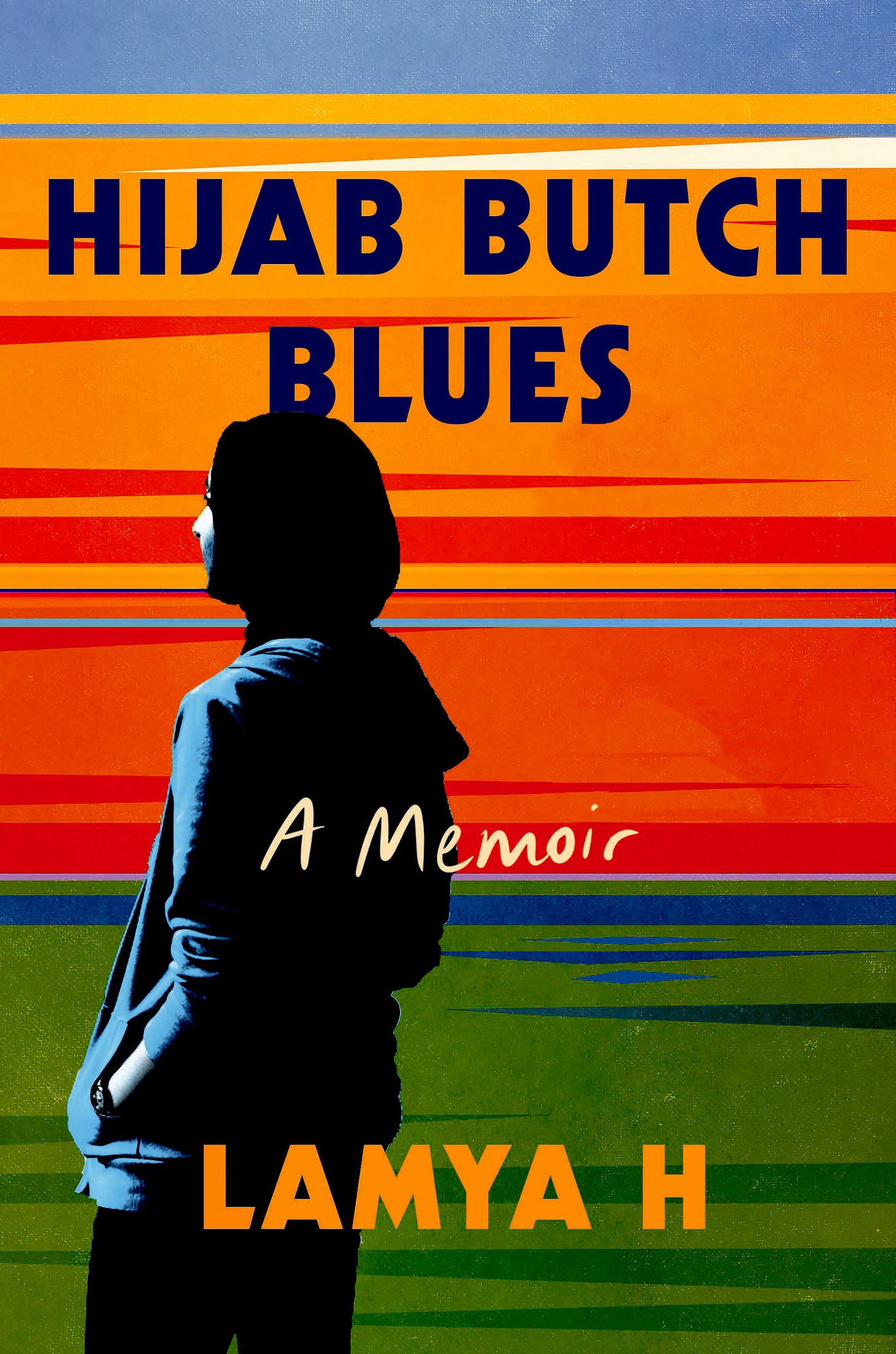

Maryam was the first Muslim dyke. Or at least she was in Lamya H’s interpretation of the Quran in Hijab Butch Blues, their memoir. Maryam, for those who don’t know, is the only woman named in the Quran.

While the memoir by author Lamya H is inherently about being a queer Muslim, it is about so much more. It’s about the intersections that occupy queerness. It’s about legible queerness. It’s queerness as class struggle, as gender inequality, as xenophobia. It’s about being a hijab-wearing Muslim among other Muslims, being queer among Muslims, and Muslim among queers.

The question, how can you be both queer and Muslim at the same time? is the assumption that we must enact our queerness in a Western way — that queer Muslims are not legitimate. We can be queer and Muslim at the same time. Being Middle Eastern, being Muslim, wearing a hijab, class, being in the U.S. and being associated with womanhood all occupy our queerness.

Lamya H’s face is nowhere, real name unknown, and they only ever say they are from a Muslim country. Reading Hijab Butch Blues felt like a homecoming. After I read Hijab Butch Blues, I put the book down, put my head in my hands, and cried.

I felt like I was having a conversation that I've never had and always needed to have. Having the opportunity to talk with them about their memoir was all the more energizing and confirming.

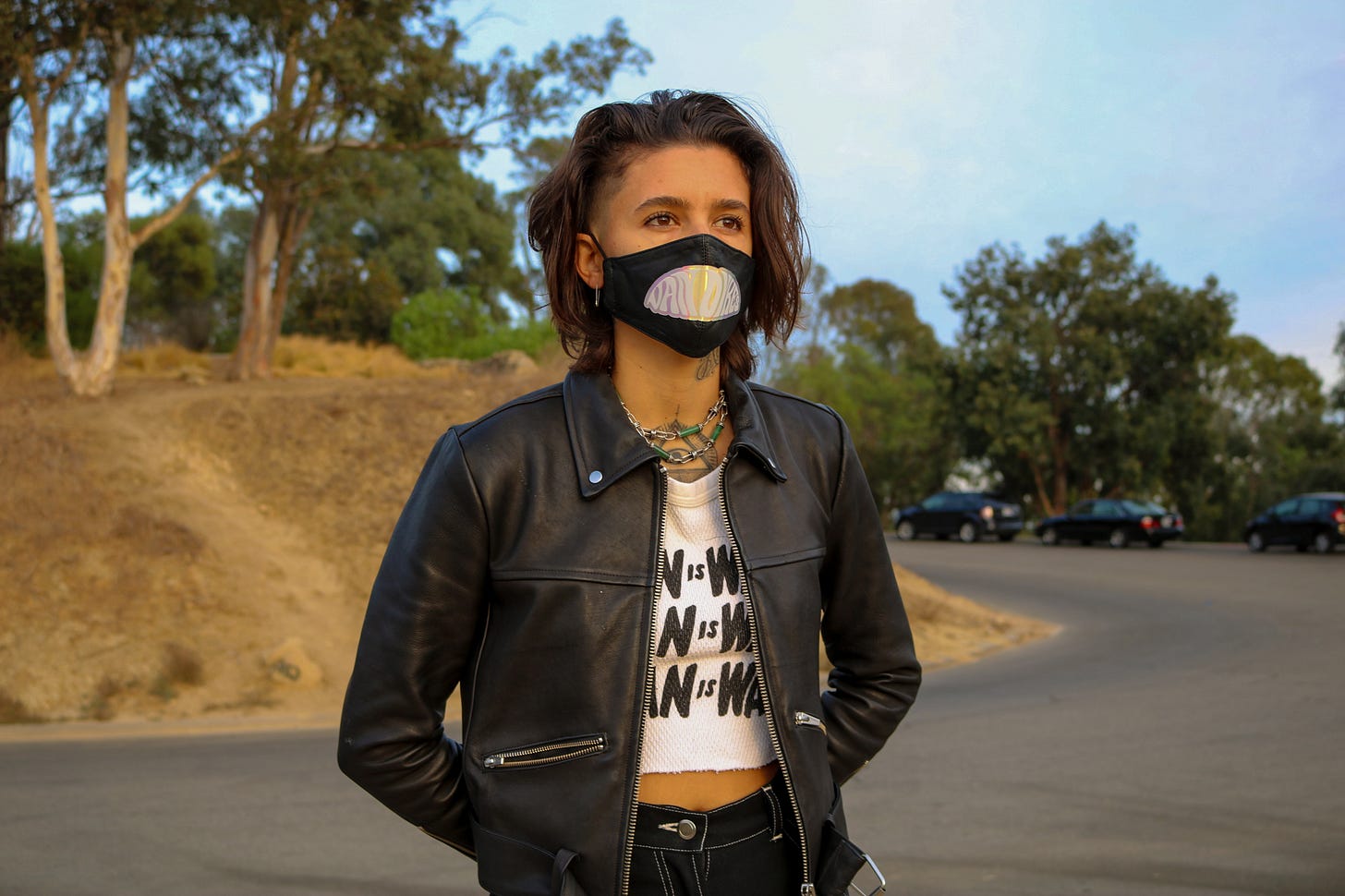

- Aryana Goodarzi, Dyke Queen Associate Editor

Aryana: In your memoir, you write about how you sought out queer Muslim groups when you first moved to New York City. I'm queer, Iranian, and culturally Muslim and never thought to seek out queer Iranian community because I didn't know there was one. I was struck by how you knew inherently that you needed queer, Muslim community to survive here. How did you come to that conclusion — that you knew there were others and you needed queer Muslim community?

Lamya H: I think that moment of finding community is so powerful, especially with people who may not have the exact same experiences as you, but have identities that are similar, or at least sort of just understand where you're coming from, and you don't have to explain things to. That was one of the most life changing things. And for me, in some ways, I feel like it was only possible because of New York. New York is such a special place in that way. I feel like for me just like walking into a room and meeting other queer Muslims was such a big part of learning to be a person in the world.

A: You talk about how among straight people/Muslims you’re not like other/most queers, among queer people you’re not like other/most Muslims. And how you are a hijab-wearing Muslim among Muslims and maybe not as feminist? How among Muslims/Western people who don’t think you can be both, your butchness is read as modesty and hijab is read within the gender binary.

You write, “To them, my hijab, my butch outfits of baggy jeans and flannel shirts, read as modest; my short hair reads as convenience; and my rants about men pass as angry feminism. When it comes to my family, my hijab is my beard.”

As someone who’s both, I would read your hijab and butch clothes as you being a queer Muslim. Can you talk more about this? How has being read like this actually helped you sometimes?

LH: That's such a good layered question. I mean, so it's interesting, because for one, I've always been really genderqueer, even as a kid. For a really long time, I didn't think I could call myself non-binary, because I wear hijab, and hijab is seen as this very particular feminizing thing. But then, the more that I thought about it, and the more that I was in sort of like spaces with other non-binary folks and other people sort of really living in like gender expansive ways, I was like, fuck that. Like why are we sort of like projecting gender onto the way that someone chooses to dress? Isn't that like, exactly what cis people do? And I think my hijab takes different forms based on the day. Sometimes it's a scarf, it's like a headscarf. And sometimes it's a beanie. And sometimes it's a baseball cap. And so I think playing with that has been really sort of gender affirming.

It's interesting, because you're right, depending on the space that I am in, there's certain ways that I'm read and that I'm not read. And I think some of the ways in which people don't read cues, like in straight spaces, for example, at my mosque, that's actually such a complicated feeling, because on one hand, it means that I can be at my mosque, and I can pray alongside people. And I can really have that sense of Muslim community, which to me is really important in terms of a marginalized identity in the US.

But then, on the other hand, it feels like there are parts of me that are just not seen, so that there's something very sad about that, too. But what's really interesting is that even in Muslim spaces, sometimes I feel like I get a look of recognition. And so that is really special too. And then what's been really interesting is also carving out alternative spaces from that. Going to places like the mosque, like sort of straight mainstream mosques has a very particular place in my life. But then there are also these alternate spaces that I've been able to carve out for myself with other queer Muslims.

So for example, for a couple of years now, we'll do an Eid prayer—that's a queer Muslim youth prayer. We'll go to a park and we'll pray in non-gender segregated spaces and have a sermon that's less hierarchical and it's less of one person talking. And that's more of a discussion. And so those spaces have also been really meaningful in terms of how I practice my faith. But it's also been really lovely to be able to pass in some ways and go to mainstream spaces as well. It feels like a kind of shapeshifting. The being-read and the being-not-read, allows me to navigate these different spaces.

A: Homophobia in Muslim countries has been used to justify imperialism and Islamophobia. You’re not out to anyone in your home country. Yet Hijab Butch Blues is about how the Quran brought you to your queerness.

You address how the need to come out to your family is one of the tensions between being gay and enacting your queerness to be legible in a white/Western way. Yet you also aren’t out to them because they might not be OK with it — do you believe that upholds Muslims as homophobic?

LH: I don't blanketly think that Muslims are homophobic. I do know exposure to different things has different effects on people. So my parents, for example, who live across the ocean, don't know any queer people; they just don't. And so the way that queerness plays out in the U.S. or in the West is very different from how they've experienced it. And so these things don't always translate. I think to me the tensions speak to a need to be generous and have empathy for people who maybe don't read queerness in the same way, or haven't been exposed to certain things.

To me, it's not that the country where my parents live is just automatically homophobic. And what's really interesting, though, is that, you know, the country where I grew up in the Gulf, the sort of rich Arab country that I grew up in, was super queer. And I think that some of the homosocial behavior hides that queerness.

But growing up, like in high school and stuff, I knew girls who were dating other girls. And I think, again, it looks so different. I don't know if applying a term as blanket as homophobic is accurate. I think there's a lot of nuance there. And at the end of the day, the tensions beg us to be more nuanced and understanding and loving. When I think of my parents, for example, I keep coming back to this idea of how do I navigate this with love?

A: Sometimes when people find out I'm queer, if they already know I'm Iranian, one of their first questions is, “Oh, my God, do you still talk to your family?” It's like, you're just inherently assuming that in the U.S., there isn't also legislation that is killing people and all of that. Sure, in Iran, it's government officials themselves, with their own hands, killing queer people, whereas in the U.S., they're still killing people. It's just indirectly, if you will, through policy and law. How do you feel about that? When you think about it in the context of the U.S., and then where you grew up? If there even are laws like that.

LH: That's a great question. I also think of the resilience of queer communities a lot. Both outside the U.S. and in the U.S.. I mean, I think of the queer community, both in the place that I grew up, and the place that I was born, and the ways in which the cultural production that is coming out is just really beautiful and nuanced. There's a lot of films that are coming out that are beautiful and nuanced. And I think of the violence of the state, and the violence of everyday people also.

The thing that I keep coming back to is the resilience of queerness. And the fact that it's everywhere and people are going to try to erase it, but it's just unable to be erased. I think about that a lot. The ways in which people are so brave and beautiful, and are carving out these lives for themselves, even under really terrible situations. And the really brilliant and beautiful organizing that we're gonna see come out of it.

A: In your book, you write about how Maryam showed you you could be gay/are gay, but you didn’t come into your queerness in a more real way, as you say, until you were around 30 years old. Did being Muslim prolong you coming into your queerness in any way or did your queerness disable you from feeling as Muslim as others?

LH: I think for me, it was mostly the one very prescriptive way to be queer. I spent a lot of my early 20s just hearing stories that were very mainstream. In terms of queerness, that was very much like, “Oh, the only way to be queer is, you have to come out to your parents in some big declaration. And you go to gay bars. And that's how you meet people.”

And just that this is the only way to be gay. I think it took a while for me to come into how I wanted to be gay and also in terms of being Muslim, I think that there are very prescriptive ways to be Muslim. And it took me a while to be like, ‘No, this is how I want to live my Islam.’ This is the kind of Islam that is important to me. These are the things that I want to put effort into.

For me, it was really a process. I'm such a black and white person. I was a lot like that as a kid. I was super rigid, like there’s good and bad; yes and no. It was really a matter of learning to break that down and realize that there are gradations between them. And the gradations are actually where most of the interesting stuff is happening. So to me, being non-binary is also really euphoric in some senses, because it breaks down those very rigid boxes. And it's like, “No, actually, here's what I'm interested in exploring.”

This is where there's potential for playing and figuring out things and fun and just being messy and being okay with being messy because mess is actually generative, as opposed to this idea of being in very rigid boxes. So to me, I had to learn how to do that both with queerness and with Muslimness. And, I think a lot about this idea of queer adolescents, where you know, straight people have their adolescence and they figure their shit out. But I definitely think there's a sort of second adolescence [for queer people] where you're just like figuring yourself out.

A: It's interesting, because a lot of the articles I've been reading about Hijab Butch Blues are like, this is about being queer and Muslim. But then when I read it, I was like, ‘No, it's about life.’ There's classism in there. There's gender inequality; there's xenophobia; there's so much in there. But it's interesting, because it goes to show how a lot of people think about what it means to be queer and Muslim at the same time.

LH: Yeah, thank you for seeing all of that. I really appreciate that. Such a thoughtful read. That's exactly what I was trying to do. Honestly. With this book, I was trying to be like, it's not just about reconciling with queerness and figuring out a way to be both, or even like answering this question. Like you said, that question my date asked me which is like, “How can you be queer and Muslim at the same time?” But actually, it's about the complicated messiness of living. And how do you do that in a world that's so fucked up? And how do you live in a way that promotes justice?

A: You wrote, “Did Maryam say that no man has touched her because she didn't like men? . . . Isn't it obvious? Doesn't it make sense? . . . Maryam is a dyke.” How do you feel about the word dyke? Do you relate to it, do you call yourself a dyke?

LH: Great question. Fun fact. The book was almost titled Maryam is a Dyke. Which I just love because I thought it was just so unapologetic, and so out there. But the big reason why I decided against that was because I just didn't want straight people saying dyke like that. It's one of those terms that I love actually and I definitely identify with it. Because, again, I just think it's so unapologetic. And so in your face, and there's this way in which it fills up your mouth, you know, like, “Dyke!”

But, there's this way in which it's also seen as this kind of dirty word. And I love the idea of reclaiming that, but there's so much violence attached to it. I really like the fact that it's been reclaimed. And I like using it for myself. It’s really rooted in a lot of history of queer activism, but it's not necessarily a word that I would want straight people to say about me.

A: The title of Hijab Butch Blues is inspired by Stone Butch Blues. Can you talk a bit about what it’s like to relate the experience of a queer white butch elder? How did Stone Butch Blues motivate you to write Hijab Butch Blues? Do you feel like you have queer elders that call to you when you’re writing? Do you bring them along with you, or in regards to Leslie Feinberg do you think you’re in conversation with them?

LH: What I love about Stone Butch Blues is that it's a book that was so effortlessly intersectional. And it's a book that's so good at writing a personal story that's about the day-to-day life of this protagonist, but that's actually deeply political and is able to zoom out through the day-to-day and write in this way that's not instructional or didactic, but that's actually just effortless about labor, about capitalism, about race, about gender, about sexuality.

I remember reading that for the first time in my twenties and just being blown away. When I was writing this book, I was also just thinking a lot about queer writing ancestors. Leslie Feinberg, Audre Lorde, whose work just like really, really influenced me.

This is my effort at trying to do that, at writing a memoir that is told in vignettes, short stories about my life. I want it to speak to bigger things. And so that's what I was trying to do in the book. And to me that really called me. I really use Stone Butch Blues as an inspiration/model for how to write like that.

A: As a queer woman, I can’t go to Iran. Your face is nowhere, and last name is unknown. You only say you are from a Muslim country. Can you talk about how your anonymity says a lot in itself about being queer and Muslim? Would you not be able to go back if you are found out?

LH: That's a good question. I think so. When I wrote this, and when I started writing, in general, I definitely knew that I wanted to write under a pseudonym. For privacy, and for Googleability. I don't want to be Googled. I don't want my address to be Googleable; I don't want my phone number to be Googleable. And I think there's this way in which I've had to fight this. I've had to fight this notion that I'm doing it because I'm scared of scary Muslims coming after me.

There's so much more nuance to that. The world is a scary place to live as a queer person, as a Muslim person, separately. And I just keep coming back to the violence that is happening against queer people in the US. All of the slurs that I've been called, walking down the street, when I'm in a beanie or something and read visibly queer. And then also, all of the slurs that had been called for being Muslim and being visibly Muslim.

It’s really interesting, because when I first pitched this book, the whole anonymity thing was such a hard thing for editors to wrap their heads around, especially when you're writing a memoir. I've had to really learn to have boundaries. I wrote about it in the chapter called “Unis.” It's just definitely something that I've had to learn: having boundaries. It's been interesting to navigate that. But, yeah, I probably wouldn't be able to go to the country that I grew up in, but I'm not sure about the country where I was born. Those are also just really hard things to navigate. And honestly speaks to another reason for using a pseudonym.

A: What made you write this book? Did you hope to engage with a certain reader (queer, Muslim, etc.)?

LH: I really started writing because I would tell the stories all the time. And I would just get really angry at injustice.

And this one time, my friend was like, “Oh, you know, Lamya, you tell all these stories, but unless you write them down, their rage sort of dissipates, and nothing happens.” It just blew my mind when she said that. I was like “Oh, I should write.” So I started writing.

I just found it to be such a good outlet for not just putting my rage somewhere, but also thinking through complicated situations.

I wrote a lot of essays at first. And then this one time, I found myself writing one of the chapters in my book, the “Hydra” chapter, which is towards the end. And as I was writing it, and really using the process of writing to disentangle my complicated feelings—that chapter is about going to visit my family with my partner and us pretending to be friends. It wasn’t easy; I was thinking a lot about the story of Hydra. And so I wrote this essay that used Hydra as a lens to really think about my complicated feelings about my visit to my family.

And so the book came about because I wrote that chapter, and I was like, ‘Oh, wait, there are so many of these other times in which I've thought through something through the lens of a story from the Quran.’

There are all of these things that I feel torn about that I could apply this analysis to. And so that's where the book came about. It was one of those things where I wrote harder, and I was like, “Oh, wait, I have so much more of this in me.” In some ways, I've been writing these stories my whole life, because I've been thinking about these characters. My whole life, I've been surrounded by their stories. And I've always been thinking of them as sort of flawed, messy humans who make decisions that I'm like, “Wait, why would you do that?” Or, or who have their own internal lives.

So that's how the book came about. And then the pandemic happened. And suddenly, I had all this time and space to write, which was really life changing, because I had one of those jobs where I couldn't go into work, and I couldn't work from home. So when the shutdown happened, I was like, “Wow, I finally have the time and space to work on this.”

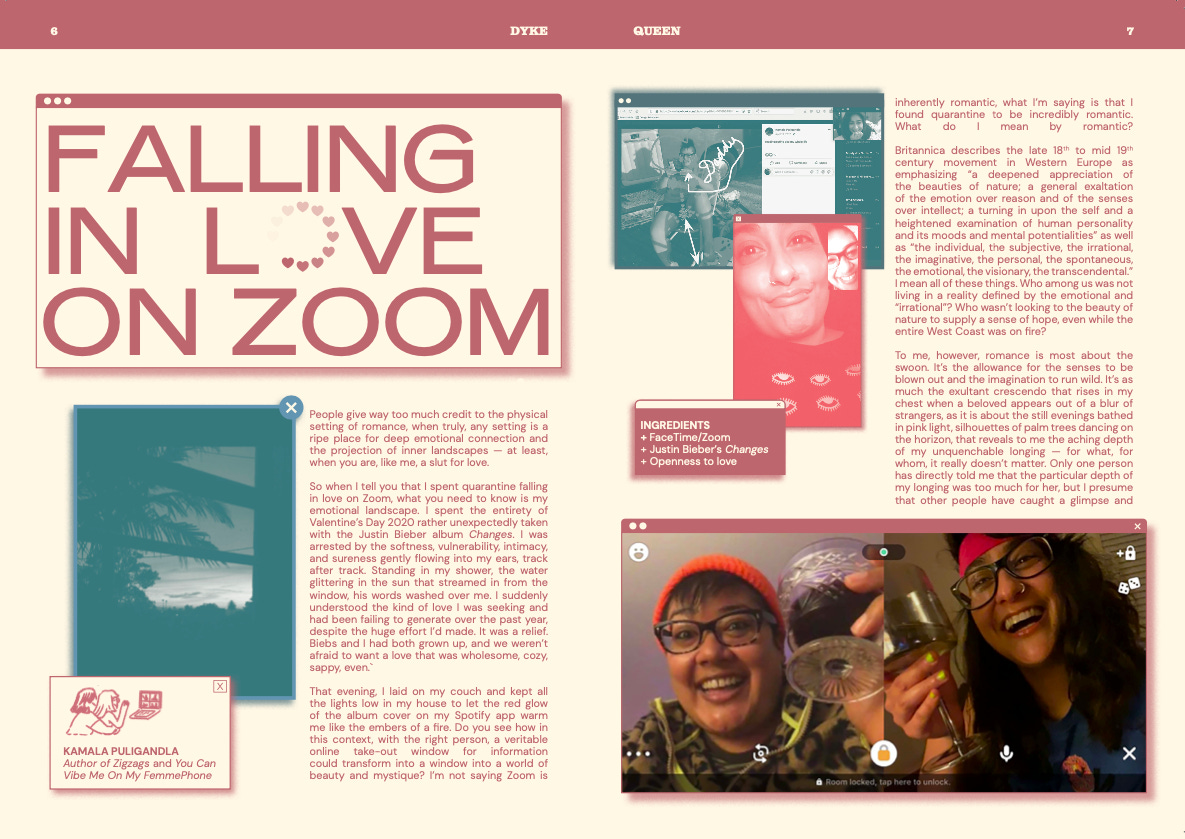

Aryana Goodarzi is the Associate Editor of Dyke Queen. Dyke Queen’s third print issue, Recipes from Queerantine, is available here. Follow us on Instagram.